Spring 2025

Long-Acting Injectable Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (LAI PrEP): Barriers to Innovative HIV Prevention in the United States

Adati Tarfa1, PharmD, MS, PhD; Jennifer L. Brown2, PhD, HSPP, FSBM; Kamal Gautam3, MPH; Adam C. Sukhija-Cohen4, PhD, MPH - HIV and Sexual Health SIG

An estimated 31,800 people acquire HIV every year in the United States (US) [1]. The Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US (EHE) initiative aims to reduce new HIV infections by 75% by 2025 and 90% by 2030 [1, 2]. Curbing HIV involves public health interventions (e.g., condom promotion and rapid HIV testing) and novel medical interventions, including treatment-as-prevention (TasP) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

PrEP is the use of antiretroviral medications by HIV-uninfected individuals to prevent HIV acquisition [3]. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Truvada® in 2012 and Descovy® in 2019 as daily oral medication [4]. Apretude®, a long-acting injectable (LAI) PrEP given every two months, received FDA approval in 2021 [5]. Recently, a new twice-yearly LAI PrEP formulation, lenacapavir, has been shown to be efficacious [6]. Despite these innovations, barriers to PrEP uptake persist due to factors such as a low perceived risk for HIV infection, less contact with healthcare providers, stigma, and cost [7].

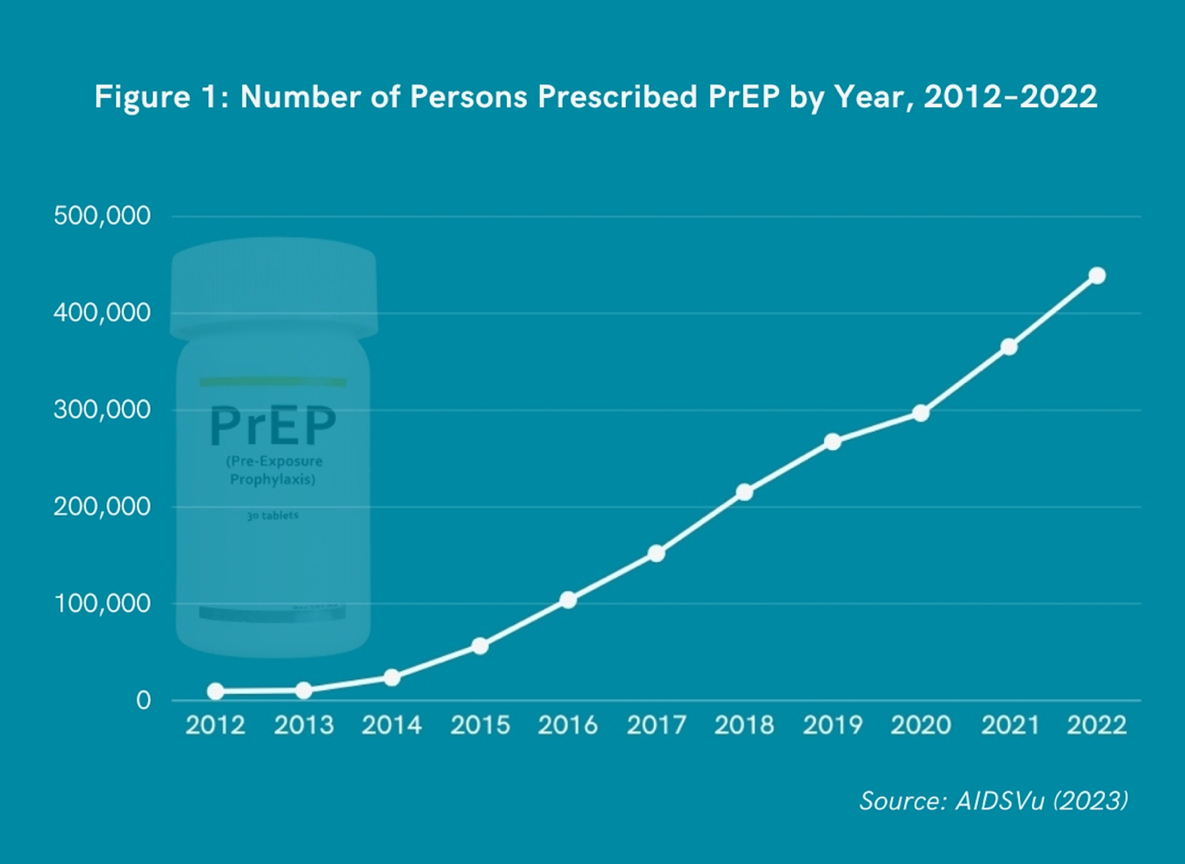

While 1.2 million people in the US could benefit from PrEP, only 36% receive PrEP prescriptions [8]. There are notable disparities in PrEP uptake by race and ethnicity. Black/African American persons represent 37% of new HIV infections [1], but only 13% of Black/African American persons recommended for PrEP receive prescriptions [7]. Hispanic/Latino persons represent 33% of new HIV infections, yet only 24% of Hispanic/Latino persons recommended for PrEP receive prescriptions [1,8]. Conversely, White persons represent 24% of new HIV infections, and 94% of White persons recommended for PrEP receive prescriptions [1,8]. These racial and ethnic disparities are particularly exacerbated among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, as well as women and those who live in the southern US [9].

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandates insurance coverage for PrEP and other preventive health services recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) without patient cost-sharing [10]. In 2023, the USPSTF recommended LAI PrEP as a “substantial net benefit” [11]. However, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will soon hear an appeal in Braidwood Management, Inc. v. Xavier Becerra, which challenges whether the USPSTF’s recommendations for PrEP and other preventive health services (e.g., cancer screening, vaccinations, tobacco cessation support, contraception) are mandated. If SCOTUS rules in favor of Braidwood, PrEP “could be subject to copays, deductibles, or coinsurance” [12], further reducing access and deepening disparities.

The rollout of LAI PrEP has been slow, accounting for only 1–2% of total PrEP prescriptions [13]. Despite the ACA’s requirements, some health insurers refuse to reimburse LAI PrEP [12]. Additionally, many dedicated HIV clinics are unprepared to offer LAI PrEP [14, 15]. Without policy changes that support stronger insurance coverage and clinic readiness, those who would benefit most from LAI PrEP will be left behind.

To our social and behavioral colleagues, here is our call to action: we must challenge systemic barriers to LAI PrEP to reach the EHE goals and develop effective behavioral interventions to promote LAI PrEP uptake and adherence. While new HIV cases have modestly decreased by 9% from 34,800 in 2019 when the EHE initiative was announced [16], disparities by race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and geography persist. The inequity in oral PrEP prescriptions will likely worsen with LAI PrEP. We must act now to advocate for equitable access to innovative HIV prevention interventions like LAI PrEP. We encourage members to contact national organizations such as the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) and the National Coalition of STD Directors (NCSD), which have historically led efforts to address gaps in HIV prevention and care. We must build on their work while encouraging local, organizational, and institutional advocacy, including within SBM. There is still much to be done, and the need for action is urgent.

Affiliations:

- Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

- Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University, IN, USA

- Department of Allied Health Sciences, University of Connecticut, CT, USA

- Center for Health Systems Research, Sutter Health, Sacramento, CA, USA

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2018–2022. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, 29(No. 1). Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/156513. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2025). EHE Overview. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- Young I and McDaid L. (2013). How Acceptable are Antiretrovirals for the Prevention of Sexually Transmitted HIV?: A Review of Research on the Acceptability of Oral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis and Treatment as Prevention. AIDS and Behavior, 18: 195-216. DOI: 10.1007/s10461-013-0560-7.

- National Institutes of Health. (2023). Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). Available online: https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- US Food and Drug Administration. (20 December 2021). FDA Approves First Injectable Treatment for HIV Pre-Exposure Prevention. FDA News Release. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-prevention. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- Gilead. (20 June 2024). Gilead’s Twice-Yearly Lenacapavir Demonstrated 100% Efficacy and Superiority to Daily Truvada® for HIV Prevention. Available online: https://www.gilead.com/news/news-details/2024/gileads-twice-yearly-lenacapavir-demonstrated-100-efficacy-and-superiority-to-daily-truvada-for-hiv-prevention. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- Ojikutu BO, Bogart LM, Higgins-Biddle M, et al. Facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among Black individuals in the United States: results from the National Survey on HIV in the Black Community (NSHBC). AIDS Behav. 2018;22(11):3576-3587.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (17 October 2023). Expanding PrEP Coverage in the United States to Achieve EHE Goals. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/director-letters/expanding-prep-coverage.html. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- Sullivan PS, DuBose SN, Castel AD, Hoover KW, Juhasz M, Guest JL, Le G, Whitby S, and Siegler AJ. (2024). Equity of PrEP Uptake by Race, Ethnicity, Sex and Region in the United States in the First Decade of PrEP: A Population-Based Analysis. The Lancet Regional Health, 33. DOI: 10.1016/j.lana.2024.100738.

- Legal Information Institute. 42 U.S. Code § 300gg–13 - Coverage of Preventive Health Services. Cornell Law School. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/300gg-13. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. (22 August 2023). Prevention of Acquisition of HIV: Preexposure Prophylaxis. Final Recommendation Statement. Available online: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (15 January 2025). ACA Preventive Services at the Supreme Court. Available online: https://www.kff.org/quick-take/aca-preventive-services-at-the-supreme-court/. Accesed 7 February 2025.

- Cairns G. (29 March 2025). Why is the Roll-Out of Injectable PrEP Taking So Long? Aidsmap. Available online: https://www.aidsmap.com/news/mar-2024/why-roll-out-injectable-prep-taking-so-long. Accessed 7 February 2025.

- Tarfa A, Sayles H, Bares SH, Havens JP, and Fadul N. (2023). Acceptability, Feasibility, and Appropriateness of Implementation of Long-acting Injectable Antiretrovirals: A National Survey of Ryan White Clinics in the United States. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 10(7). DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofad341.

- Keddem S, Thatipelli S, Caceres O, Roder N, Momplaisir F, and Cronholm P. (2024). Barriers and Facilitators to Long-Acting Injectable HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Implementation in Primary Care Since Its Approval in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 95(4): 370-376. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000003370.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (4 June 2021). Estimated Annual Number of HIV Infections ─ United States, 1981–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(22): 801-806. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7022a1.htm.

- AIDSVu. Prevention & Testing in the United States. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). Available online: https://map.aidsvu.org/profiles/nation/usa/prevention-and-testing#1-1-PrEP. Accessed 7 February 2025.