Summer 2024

Employing Social Media to Communicate Evidence: Advice from @steph.compton.phd

Alyssa M. Button, PhD; Hanim E. Diktas, PhD, MS; Jessica Balla, MA; Marc Kiviniemi, PhD, MBA, CPH, FSBM; John Updegraff, PhD - Theories and Techniques of Behavior Change and Intervention SIG

As scientists and practitioners, it can be frustrating to scroll through the abundance of misinformation available online. We know there are evidence-based solutions, but often struggle to translate scientific information for public benefit. Stephanie Compton, PhD, RD, LDN, a postdoctoral cancer researcher at Pennington Biomedical Research Center with expertise in nutrition and metabolism, shared some key takeaways from her experiences with science communication via social media.

Communication is an art and a science:

Dr. Compton has learned to identify which strategies work, and which are less effective, in communicating information for a target audience on social media. This can be applied in other contexts too, with Dr. Compton stating: “Grant writing is just a different form of science communication.” She tailors her information to the reader who wants to know—what is the context of these findings, and how can they be used? As more funding organizations require a general audience abstract for grant applications, this lens for writing is extremely useful. Other translational skills of science communication via social media include managing lab-related time, networking online with other professionals, designing and developing a professional brand, and creating engaging participant-facing materials.

Engagement:

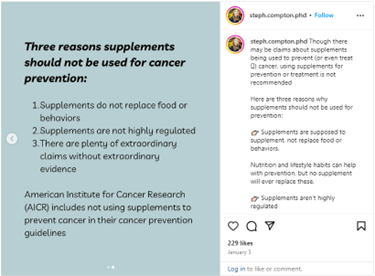

Science communication via social media can help overcome barriers to public engagement that result from journal paywalls and complicated reporting styles. Communicators can help the audience by strategically building knowledge through multiple slides or posts. For example, Dr. Compton's approach may include creating a first post describing what is known about the topic, then explaining how it's measured and why it's measured that way, and finally discussing the implications. She posts this information in succession so a viewer can easily go from one post to the next.

Time management:

There is more to scientific communication than content creation! Additional time includes answering questions and checking on how well a post is doing. Social media runs on a 24-hour cycle, where people quickly move on to other newsfeed topics, which helps to manage post engagement. When time is tight, content can be repurposed, or posted to a 24-hour story rather than a “permanent” post. Most scientists do not get paid for time and effort spent engaging with followers online. Dr. Compton sees her work as another form of community outreach and service to the field, where scientists can speak to thousands of people at once, stating: “I think social media can be thought of in a similar way to a presentation at a conference, it’s just a different audience in a different medium.” Administrators may consider including the quality of communication and the quantitative reach of social media posts in promotion and tenure decisions.

Social media runs on a 24-hour cycle, where people quickly move on to other newsfeed topics, which helps to manage post engagement. When time is tight, content can be repurposed, or posted to a 24-hour story rather than a “permanent” post. Most scientists do not get paid for time and effort spent engaging with followers online. Dr. Compton sees her work as another form of community outreach and service to the field, where scientists can speak to thousands of people at once, stating: “I think social media can be thought of in a similar way to a presentation at a conference, it’s just a different audience in a different medium.” Administrators may consider including the quality of communication and the quantitative reach of social media posts in promotion and tenure decisions.

Validity:

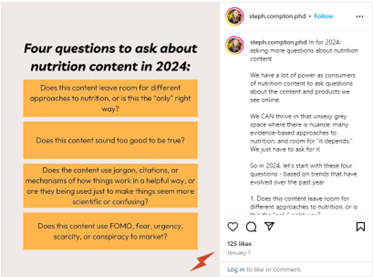

Savvy media users can assess the validity of posts on social media by checking whether: the user has relevant education and/or backgrounds, their statements lack nuance, and their openness to multiple points of view. Dr. Compton also suggests users should be skeptical of fear-mongering and quick solutions to complex problems.

By sharing evidence-based findings online in a reader-friendly format, Dr. Compton shows that scientists can disseminate useful messages, improve communication skills, and provide service to the field and community.